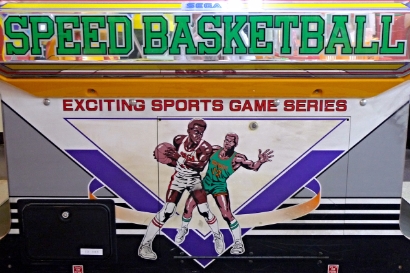

Tokyo Game Centre #07: Speed Basketball

Speed Basketball

Here’s what we’ve got: there’s a big thing like a table football table, and two players stand on opposite ends with a button and a trackball each. In a certain sense, Speed Basketball’s an extremely simplistic rendition of the sport, but, conversely, it’s characterised by exceptional — almost obsessive — realism.

Total, if rather focused, realism

First of all, the play area is portrayed on a 3D display which gives a very real impression that a miniature basketball court is actually contained under its glass bubble. This is fantastically convincing: you can bob and weave your head around as much as you like and it won’t show any flaws. So convincing is it that I wonder if the glare on top of the curved surface is there by design, to encourage you to move around and see the court from different angles.

Secondly, the realism goes beyond the visuals to an almost stupidly thoroughgoing physics model.

What you do

The game mechanics are simple — this is not basketball as you know it. The ball can only be played when at rest, and can only rest in a small number of fixed positions. There are no people on the court — only one ring of light per player that can be moved with the trackball to any of the possible resting positions in order to play the ball. When the ball’s played, each player can only fire it in one fixed direction from each position.

You might wonder, then, where the room is for a detailed physics model. Well, Sega took that very basic system, and represented it with such ridiculously fine-grained specificity that they even modelled parts of the mechanics that might at first seem irrelevant to the game. Let me explain…

The fun is in the details

I read an interview with Bennett Foddy a while ago and he said something that really stuck with me. He said that his game Poleriders “is designed to be slightly random… Being really great in Poleriders means you win nine times out of ten; it doesn’t mean you win every time.”

Multiplayer competitive games thrive on that element of chance. There has to be something unpredictable, left down to luck. That’s what keeps you coming back: even if your opponent establishes a consistent superiority, there’s both a hope you might win against the odds, and an excuse that they’re not really superior anyway — they’re just lucky. You’ll always try one more go, even on a monstrous losing streak.

This is where Speed Basketball’s attention to detail comes in: from the tiny, apparently pointless features of the physics engine emerge consistent, fair, but not completely predictable complexities. Perhaps the most important example is that your button doesn’t just control the ball and make it move where you want. Instead, there is actually — if you look very closely — a tiny hammer under each of the ball’s resting positions. That hammer flicks up on the button-press, in a fraction of a second, to strike the ball. It’s a bizarre thing to model, but the result is that if you press your button, let’s say, 100 ms slower than your superior opponent who’s focused on the same position, they’ll hit the ball cleanly in the direction they wanted. However, if you hit your button only 50ms behind your opponent, your little hammer will get up just in time to fractionally obstruct their shot and minutely divert the course of the ball.

Conjuring a world

So, why model all that? The speed the hammers move — in their tiny fractions of seconds — is actually fundamental to the mechanics of the game! Even if you’re always the slower player, you can be just quick enough to stop a point from being scored — or you might interfere up-court at just the wrong moment and send a should-be-impossible long-range shot sailing into your own net. The point is that even a weak player can corrupt the certainty of their opponent’s victory, and introduce the magical randomness that gets you hooked.

The hammers — almost invisible though they are — make sense of this mechanic and communicate it to the player, conjuring a world ripe with the possibility of those delicious freak events. Yes, it’s a bizarre level of detail, but it does a job, and does it very effectively. There’s a clear, fair system underpinning all the action, but the sheer complexity of the physics model — and the subtlety and precision of the 3D display showing it — mean that you can’t take anything for granted in Speed Basketball, and you need to be unwaveringly alert if you want to win.

A puzzle

The confusing part of this whole thing is that I have no idea how this technical feat is achieved. More realistic physics I have never experienced; a more true-to-life 3D display I have never seen. And the most confounding thing of all is that Sega managed to build all this with 1992 technology!

Such a realistic 3D display. I imagine it’s done with polarised mirrors or something.

Okay, okay.

I wondered at the the end of last week’s post whether Speed Basketball should even be called a videogame. The fact that it certainly could have been a videogame seems to count for something in my mind. And everything I said about the mechanics and the balance and the luck and the addictiveness is completely true: this is a masterclass in competitive gaming.

And you get close to 10 minutes for your ¥100.

Next week: rhythm action. But not nerdy, Bemani rhythm action; the casual rhythm action of the bizarrely mundane.

(See all postcards from the game centre here.)

🎮💡

Photographer and writer covering Tokyo arcade life – the videogames, the metropolis and the people