‘Rez’: A Story Told Like Games Tell Stories

Rez (2001) brings out the gamer in me. It’s a perfectly designed son-et-lumière spectacle, but it’s also a videogame, and in one of the most firmly established genres: the rail shooter.

As a child I was captivated by Space Harrier (1988) on my friend’s Atari ST. It was colourful, fast, and exciting. I felt as if its “Fantasy Zone” spread out forever, full of mysteries. Just as we thought we would make some progress, it always seemed to be time for me to go home. The mysteries went unsolved. Space Harrier caught my imagination as if it held the key to transcendence or had some kind of ultimate, joyful revelation hidden away in its final stage. That’s what games did to us as kids.

But it was actually just another dumb beige disk in the pile, and we imagined the magic for ourselves. It was just a rail shooter. But what if a game like that really meant something?

A rail shooter story

I like to talk about two problems for storytelling in games. The hero problem is the tension between a narrative of heroic success and mechanics where the protagonist might fail. This comes up in most games. The Freeman problem is the tension between authored scenarios and player freedom within them. E.g. when mechanics allow for stupid behaviour by the protagonist which is not in line with the story the author wanted to tell.

Some indie or arty games shed light on these problems in interesting ways — The Stanley Parable (2013), for instance, or Braid (2008). Rez solves both problems, but without being fancy or clever. It’s not a game that’s even thought of for it’s story. It’s not even of a genre usually though of for stories: it’s just a rail shooter, but it means something.

Rez is a tremendous work of storytelling. In contrast to other popular games-as-art poster children, whose good artistic elements still jar against their gaminess — Ico, Shadow of the Colossus, Braid, for example — it takes familiar and polished videogame tropes and lets them become a narrative on their own. It proves that games don’t need to hide their history to do something valuable.

The story and its telling

Rez’s otherworldly story is about a computer system which is being overwhelmed with information, and is wrestling with the traumas of worldly understanding and self-awareness. The player is a hacker infiltrating the system to locate the central AI and shut it down.

In playing the game, the player is bombarded with information in the form of typically rail-shooter enemy waves and attack patterns, dressed up with Tron-style computer-space graphics and hypnotic, rhythmical sounds quantised to the techno beats of the electronic soundtrack.

The narrative is developed in vague passages of text between playable levels. It deals with the evolution of life, intelligence, and consciousness, the puzzles of self-understanding, and the possibility of ultimate transcendence in their solution.

The playable stages do not add concretely to the narrative, but instead develop the story thematically. They allow the player to learn, understand, and develop mastery, so that by the time the central AI is located, the player shares with it a sensation of adeptness and of oneness with the system of the game.

Completing the game provides a closing cinematic and rolls the credits, but then finally displays a single line of white text on a black screen:

“She still lies trapped within the system…”

So inquisitiveness demands another play through the game.

The repetition does nothing to dismantle the narrative because it is set out so vaguely, and is all about progress, development, and revelation. Replaying only strengthens the effect of the interaction, developing the player’s ability further, and bringing you closer to mastery and a complete understanding of the world.

The player is primed for transcendence, for the potential escape from the system that is tacitly promised in the closing text. Your hope is that if you do better — if you achieve perfection — then the AI will join you in your release, sharing in perfect mastery of the system you both inhabit.

The hero problem is avoided because there is not a narrative of success in each attempt — only a narrative of overall completion. If the player gives up before getting there then the story remains unfinished. A restart of the game is not a restart of the narrative — it’s a continuation of your development as the hacker in the system.

The Freeman problem is avoided because the player has no freedom to interfere with the author’s control. It is the essence of a rail shooter that you are taken along as the creator dictates. If the game is on rails then it makes sense that the story is too.

Developing the metaphor

What I’ve described so far falls under the system of the game — the interactivity mechanics. Those mechanics are set perfectly in line with the story of the game. The metaphor, the non-essential superficial characteristics of presentation are also brilliantly executed.

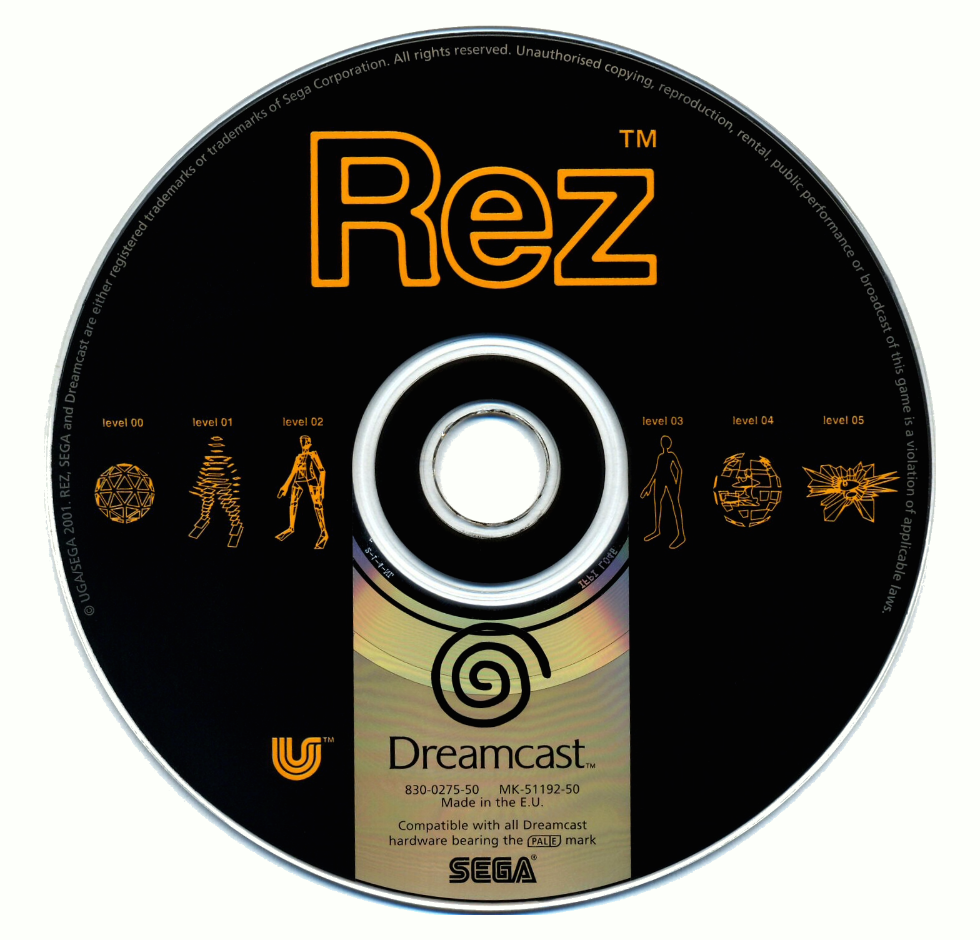

Developing the theme of evolution, the player-character levels up during play from a rudimentary polyhedron, through increasingly complex humanoids, to a figure of religious enlightenment, and then beyond, to a form of pure abstraction. The beam fired from the player-character progresses in tandem, from inefficient, snaking lines, to straight, direct flashes, to, with the final character form, the mere effect of removing targets, with hardly any visual cue at all — only sounds.

The six forms of the player character as depicted on Club Sega, where they have a good write-up of the game

The sound design as a whole works perfectly towards the game’s themes. The samples and rhythms in the music grow in sophistication and complexity as each level progresses, and also from one level to the next.

Visually, too, the five levels’ predominantly abstract appearances become progressively more concrete and organic, until sound and visuals come together in the final stage, full of animalistic mechanical targets, wireframe vegetation and geographical features, and musical voice samples attached to player actions. It’s a general impression of humanity itself coming together in the lead up to the game’s climax.

The final boss — the AI at the centre of the hacked system — takes on a broken human form, representing its struggles with self-consciousness, self-destruction, and transcendence.

A cop-out?

Separating narrative progression from player control could be considered a cop-out: the problems for interactive storytelling are avoided but not solved.

An interactive story is normally supposed to allow the player to affect the direction of the narrative, but in Rez, you can’t. The story goes along on its rails, while a refined interactive experience engages the player and pulls you into its world. For me, this is a legitimate approach to interactive stories: after all, it’s great storytelling, it’s interactive, and it’s great because it’s interactive.

The player gets a direct experience of understanding and mastery, leading up to that final humanistic stage, and a stepping stone to climactic transcendence in the narrative if you can truly master the system of the game. Rail shooters are the kind of game where expert players focus, obsess, perfect their technique, and have their own little peak experiences. Rez is the only one that formalises, celebrates, and guides that experience. It leads the player to transcendence, reflects that transcendence in its narrative, and acknowledges perfection with a secret reward.

Furthermore, the absence of player control over narrative isn’t accidental or meaningless; it’s deliberate and conspicuous. It makes the story’s progress inevitable, implying a higher power, a grand system much bigger than the player and with a grand existential purpose.

All the videogamey quirks and all the limitations of Rez’s form are are not just dodged, but harnessed, for an artistic result that would be completely impossible in any other medium. That’s why Rez is so captivating, with transcendence, joy, and revelation hidden away in its final stage — and in a rail shooter! A rail shooter!

As I did with Space Harrier as a child, gamers are used to imagining that videogames are this good. It would be easy not to notice that this one really is.

🎮💡

Photographer and writer covering Tokyo arcade life – the videogames, the metropolis and the people