The Drive to Quest

Earlier this month, Arin Hanson (A.K.A. 1.5m-subscriber youtuber Egoraptor) posted a 30-minute video critique of the Zelda series, focussing especially on Ocarina of Time (1998).

It’s a bit rambling compared to his other ‘Sequalitis’ videos, but it’s just as high-paced, passionate, and incisive. (For a shorter intro to Egoraptor, try his Castlevania IV one.)

I don’t agree with his analysis.

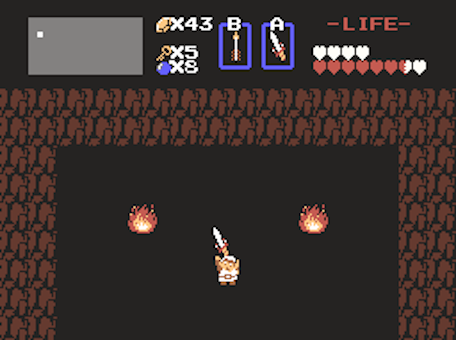

Link discovers the Master Sword on the NES

Link discovers the Master Sword on the N64

Ocarina’s bullshit

Among Hanson’s criticisms is an objection to the over-the-top ceremony of Link opening treasure chests in Ocarina of Time. An extended animation and musical cue accompany every opened chest — a feature absent in A Link to the Past (1991).

(15:41) A treasure chest in and of itself is a mystery and a sense of suspense. […] Simply walking to the chest is all the suspense you need. […] The feeling of suspense [in Link to the Past] is real, and very valid.

(16:17) Ocarina decided to add in bullshit! Link opens up the treasure chest and is all like “What the fuck is… What is this? Oh my god! I’m amazed!” Who cares that he’s amazed? I wanna be amazed!

This gets at his broader point: that Ocarina takes pains to tell you what to care about, instead of making you care with its gameplay.

Adventuring

Hanson goes on to argue in this vein that the whole sense of adventure in Ocarina is diminished by over-eager exposition of purpose in on-screen text and cinematic showboating. In fact, he levels the same criticism at A Link to the Past, and argues that only the first game in the series — The Legend of Zelda (1986) — got adventuring right.

(2:35) Exploration still exists in Link to the Past — and God knows it’s required to beat it — but if a game is telling you to do specific things with marks on a map and a sequence of which things to do and specific instructions, you’re not discovering a world; you're being taken on a tour.

(20:10) Ocarina’s story provides you with a context to your quest […] but it refuses to acknowledge the player’s innate sense of wonder, and drive to quest, to fight. Players […] want to enter a dungeon, see what’s inside, and succeed against enemies.

Hanson’s saying that games should elicit an emotional response, not assert one, and on top of that, they should elicit that response using game mechanics and interaction. He dismisses what the games are doing with their superficial presentation — with their metaphors — on the grounds that their underlying mechanics — their systems — must do those jobs for them to count.

Link completes the Triforce with minimal ceremony on the NES

Link completes the Triforce with astonishing 3D graphics on the SNES

I don’t think that’s right. System and metaphor both have roles to play in engaging the player, and when they’re used together the effect can be phenomenal.

In a previous post about this, my example was Thomas Was Alone, but here’s another example. In the case of Zelda, all that’s happened since the first game on the NES is that the metaphor has been brought into alignment with the system. This is an improvement.

What’s really going on

In the first Zelda, the metaphor did very little work at all. Hanson loves that fact:

(0:59) In Zelda you were an adventurer and, well, seriously, that much wasn’t even explained. You were just a green dude, walk into a cave, old dude goes ‘Hey, take this!’ You’re like ‘OK.’

(3:20) It’s not the kind of game that holds your hand. There’s no explanation or even really like a goal, but there’s adversity everywhere, and you can approach it any time you want, whether you’re prepared or not. You run the real risk of facing off against something that will kill you — in a fucking second! It’s fucking awesome!

There’s nothing to stop you from going somewhere except for the fact that it’s really difficult. And you don’t know if you need to persevere because it just is hard, or if you should come back later when you’ve found an easier section that will reward you with a new ability that you need. “Adversity” is the right word — it’s brutal.

So Link to the Past tightened up the structure. At the level of the system, instead of just really hard sections that encourage you turn back, you get out-and-out inaccessible areas and things that are strictly and clearly impossible until later stages of the game. But instead of just punishing you for wondering if you can, admonishing you for your adventurer’s instinct like the first Zelda, Link to the Past communicates with you in it’s metaphor as well as it’s system. You are told in dialogue that you are on a quest, and that you will need to complete certain steps along the way.

You even get a map with flashing numbers on it telling where you’re going next and where you’re going five steps after that!

OK, so that’s a bit heavy-handed.

A Link to the Past and Ocarina didn’t replace the player’s experience of achievement with a narrative of progress existing only in the metaphor. On the contrary, it added to the metaphor an explicit framework for making sense of the progression the player feels in the game. The system and metaphor are brought into line with one another.

This was an enormous step up in sophistication over the rudimentary and punishing NES game. Instead of a brutal world that you would feel privately relieved to have survived, you are given a proper framework for your progress, a story to enhance what you are actually experiencing when you play, and a ceremony of success and closure to accompany your satisfaction.

Systems of interaction are special to videogames, and Hanson seems to want them to carry every aspect of what any game does. But I don’t think he’s found a universal rule that the Zelda series has broken. What he does is highlight a change in direction between Zelda on the NES and A Link to the Past. Maybe it’s a shame the direction changed, but that’s a matter of taste. Nothing in Link and Ocarina undid the first game’s work, and what was added was evidently added with coherent purpose.

The drive to quest

Hanson covers a lot more ground in his video, but one thing I really love about this thread of argument is his craving for the player’s “drive to quest” to be acknowledged. I suppose where we differ is that he thinks making the quest explicit in the metaphor undermines the successful work of the system to give it structure, whereas I think it enhances it.

But I agree that the drive to quest is real — and I love that turn of phrase. I also agree that videogames can provoke that drive in a special way. It’s true that our reason to conquer Death Mountain may just be the same as Mallory’s to conquer Everest: because it’s there. But that doesn’t mean we can’t dress the quest up with all the lights and sounds that videogames also do so well.

🎮💡

Photographer and writer covering Tokyo arcade life – the videogames, the metropolis and the people